Maulana Ubaidullah had been caught with letters revealing a plot to overthrow the British Empire.

The plan? To ally with Islamic nations from around the world and launch an uprising against the British.

Watch video now

Around 100 years later, he and others like him were honoured by India’s president for their anti-colonial efforts.

He was part of the Silk Letter Movement which Indian’s then-president, Shri Pranab Mukherjee, described as: “a glorious chapter of India’s history of freedom struggle,” which truly reflected “…the multi-cultural and multi-faceted dimension” of that struggle.

But what was the Silk Letter Movement?

Following a quashed uprising against the British East India Company in 1857 and increasing colonial controls on education, some Muslims started to set up seminaries in order to protect traditional Islamic values from British interference. The most successful of these was around 150km north of Delhi in a town called Deoband, established in 1867.

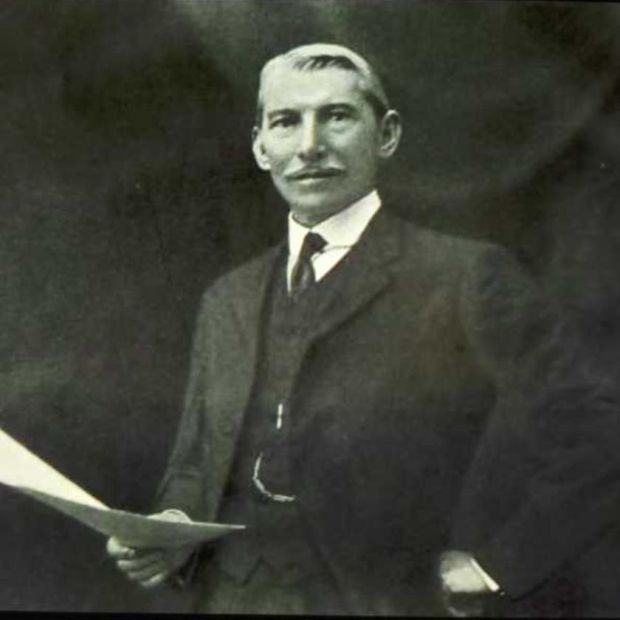

The ever-suspicious British Empire, sent spies to infiltrate its classes, but reported nothing of interest until 1915, when evidence came to light of a ‘change’ in attitude, which reached the top including its president – Maulana Mahmoodul Hasan.

A year later, Maulana Ubaidullah Sindhi, a Sikh convert to Islam, had been caught with three silk letters in the lining of his coat.

“A group is to liberate India. This group has moved to establish centres in India to make alliances with other powers. Another group called al Janout al Rabania is a special Islamic assembly based on military principles. Its first object is to create an alliance amongst Islamic kings. This is the only way of inflicting an effective blow against the infidels of India.”

The plan was to send envoys, to both Islamic powers and Britain’s World War One enemies to invite them to join in the struggle against British rule.

At the onset of the First World War, Maulana Ubaidullah, Maulana Mahmoodul Hasan and other key figures of Deoband left India to seek alliances with Afghanistan, Germany and the Ottoman Empire.

Letters described how Maulana Mahmoodul Hasan would be a military general with subordinates in Tehran, Kabul and Istanbul, and eventually India itself, which Hasan later denied when captured in Makkah and interrogated in Cairo.

When Maulana Ubaidullah’s letters were first discovered in British-ruled Multan,

they were described as ‘childish rot’ by Sir Michael Francis O’Dwyer, the Governor of Punjab. But the Department of Criminal Intelligence in India thought that they were much more serious. British officials produced thousands of pages of analysis, attempting to understand the significance of the letters for the future of British rule.

“The objects of the conspiracy to wage war, to attempt to wage war and to abet the waging of war against the forces of his majesty or to dispossess his majesty of the sovereignty of India were to be affected by exciting religious fanaticism among the Muhammadans of India by perverted teaching from the Quran and in other ways by stirring up hatred against the British government among the frontiered tribes in Afghanistan, by seeking war-like assistance from the Turkish Empire and by collecting funds for these ends.”

After the discovery of the ‘conspiracy,’ key Deoband figures, including Maulana Mahmoodul Hasan, were arrested and deported to Malta, until the end of the First World War, the British fearing a backlash if they were to be imprisoned in India.

The story of the Silk Letter Movement highlights the British Empire’s long history of viewing its Muslim subjects as ‘fanatical.’ But the Indian government’s 2013 commemorative Silk Letter Movement postage stamps showcased a different view of the affair… one of celebration of the movement as part of a struggle against an oppressive regime and as a nationalist contribution to Indian independence.