When you think of a Thomas Cook holiday, you probably don’t think of a round-trip ticket to Makkah. But leading up to the height of the British Empire, that’s exactly where Thomas Cook could take you…

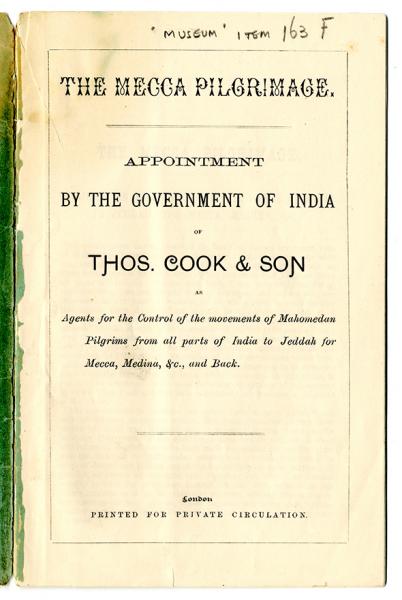

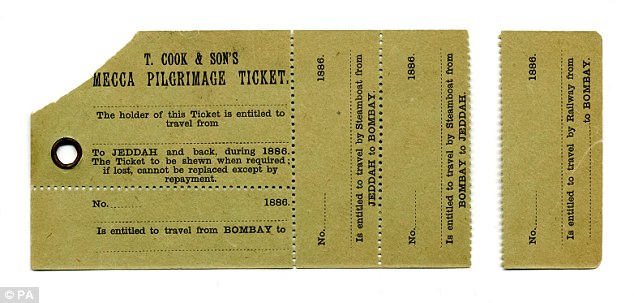

In its almost 200-year history, the world’s first modern travel agency sold millions of trips to British holidaymakers, but one of its very first “package holidays” helped India’s colonial Muslim subjects perform Hajj at the request of the British Government.

But what supposedly began as the imperial power’s attempt to stop the spread of disease within its colonies, to improve the safety of pilgrims and to curb the exploitation of the poor, later revealed itself to be something more than that.

Britain ended up facilitating the pilgrimage in an ineffective attempt “to gain legitimacy among its Muslim subjects.”

In 1886, in the wake of a scandal surrounding the near-sinking of a pilgrim ship, Thomas Cook was given a contract by the British government to arrange travel logistics for Muslims living in Colonial India, enabling them to perform Hajj.

But this was not the first time that the British had requested the assistance of Thomas Cook to aid them in state affairs.

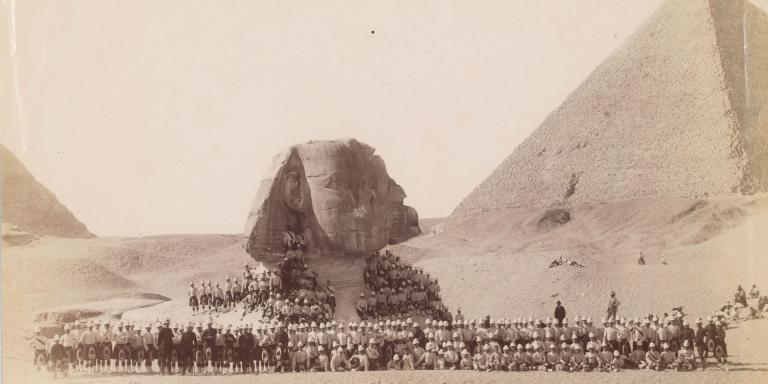

Just four years prior, under the directorship of Cook’s son, John Mason Cook, the British Government hired the company to transport Sir Garnet Wolseley and his staff to Egypt for the military campaign that would later result in the British occupation of the country.

The firm was once again called upon to organize the evacuation of the wounded,

after an Egyptian rebellion against the British. And in Sudan, Thomas Cook’s imperial logistics were used to organize a relief expedition to rescue General Charles Gordon from Khartoum.

In the words of historian, F. Robert Hunter

“Tourism was inseparable from the west’s conquest of the Middle East.”

Also inseparable, was Britain’s regulation of the Hajj from its desire to exert authority and surveillance over its Muslim subjects.

Even after Thomas Cook ended its Hajj contract with the British government just seven years after the venture began, the British regulation the Hajj did not come to an end.

For many more decades, Britain managed the Hajj in an attempt, to appear as a “friend and protector” of Islam.

Although pilgrim safety, exploitation and disease, were cited as Britain’s main concerns its continued infiltration of Hajj institutions suggested different intentions.

From the 1860s, Britain used the British consulate in Jeddah, Arabia, not only to exercise influence in the area, but also to monitor pilgrims who might pose a threat to British imperial interests.

While Britain and other European Colonial powers continued to surveil pilgrims for disease and infection, by the turn of the century, Britain feared a greater infection – an infection not of the body, but of the mind -of anti-colonial ideology and so-called “fanaticism.”